The $3 Billion Subscription You Never Signed Up For

If you’ve ever forgotten to cancel a subscription, you know the feeling.

You meant to pause it.

You assumed you’d get a warning.

The charge hit your card anyway.

No catastrophe. Just mild annoyance. You shrug and move on.

Now imagine the same logic applied to prescription drugs.

You don’t get stuck with a movie you didn’t watch or a newsletter you didn’t read.

You get medication you didn’t need.

Shipped earlier and earlier.

Paid for automatically.

And piled into drawers, shoeboxes, and medicine cabinets across the country.

That’s not a hypothetical. That’s what a recent Wall Street Journal investigation found is happening to Medicare patients right now.

But the real villain here isn’t the mail-order pharmacies.

As usual, it’s the PBMs and insurance companies — with seniors and taxpayers footing the bill.

What the Investigation Actually Found…

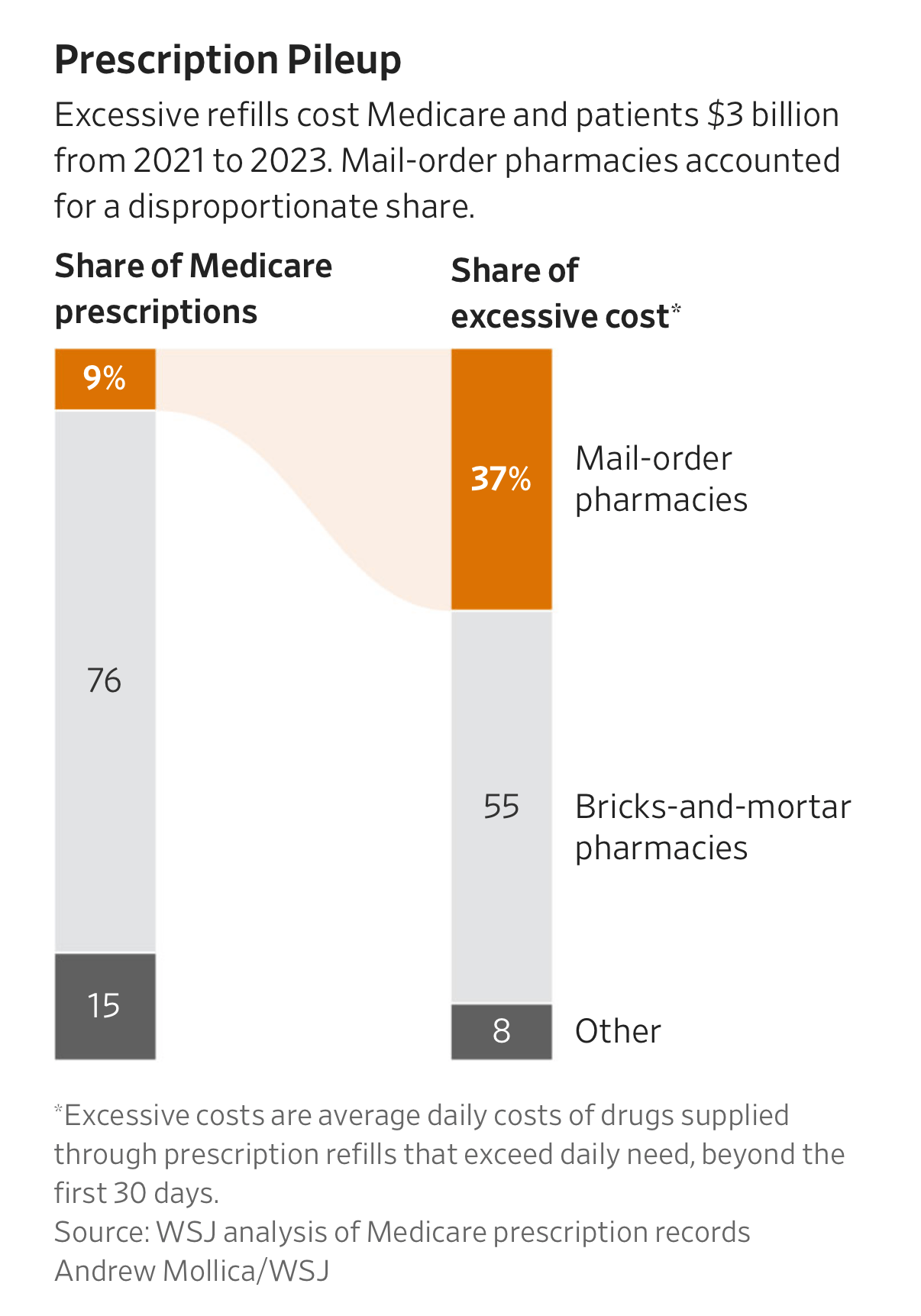

Between 2021 and 2023, U.S. pharmacies dispensed roughly $3 billion worth of extra prescription drugs to Medicare patients via early refills.

What does that mean?

It wasn’t fraud.

It wasn’t patients abusing the system.

And it wasn’t doctors writing reckless prescriptions.

It was automatic refilling, optimized to ship more medication than patients could possibly use.

Here’s the most important data point:

Mail-order pharmacies filled only about 9% of Medicare prescriptions, yet they accounted for 37% of the excess dispensing.

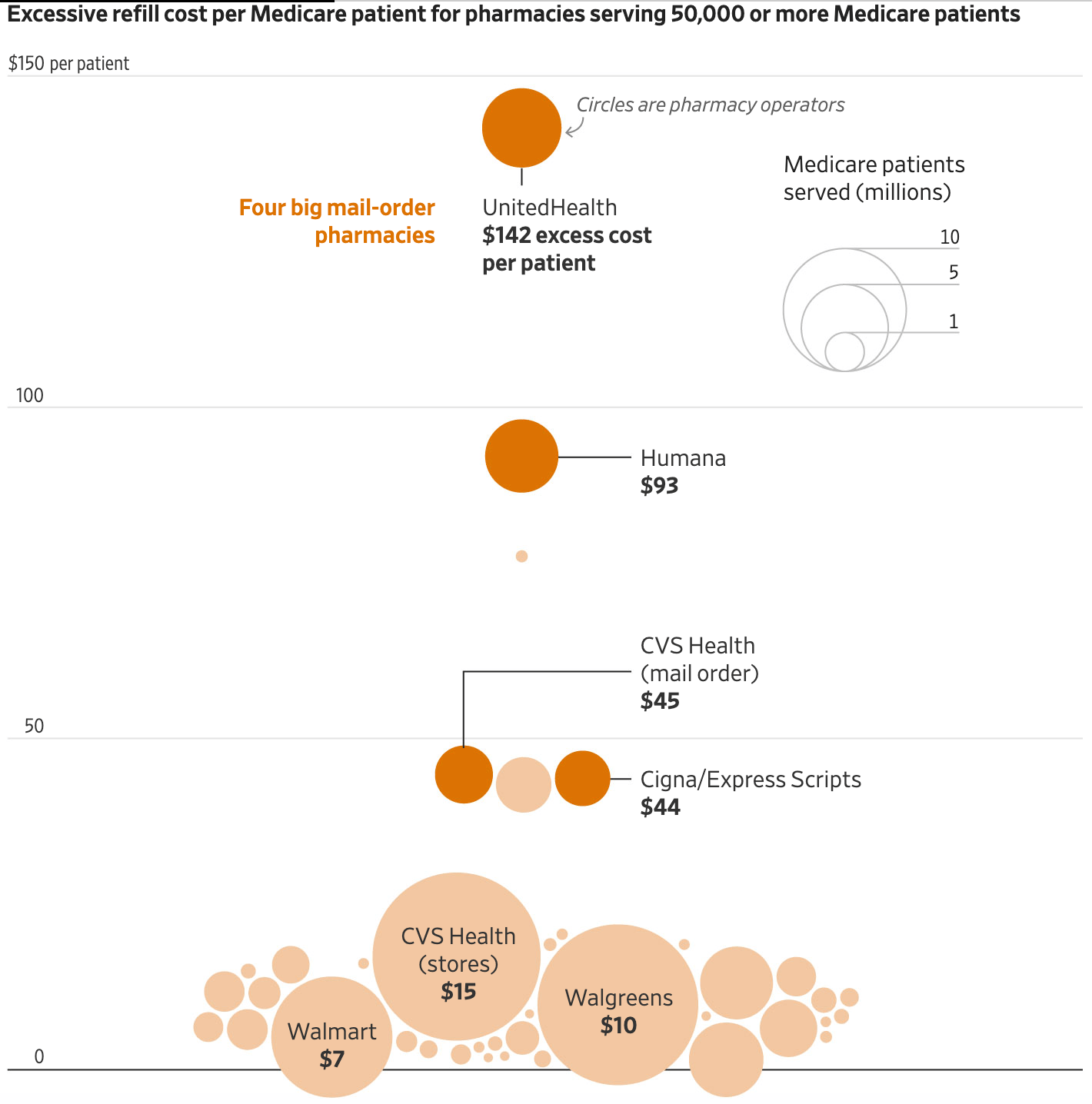

The biggest offenders weren’t mom-and-pop operations. They were mail-order pharmacies owned by the largest insurance companies in America:

UnitedHealth (OptumRx)

Cigna (Express Scripts)

Humana (CenterWell)

CVS Health (Caremark mail order)

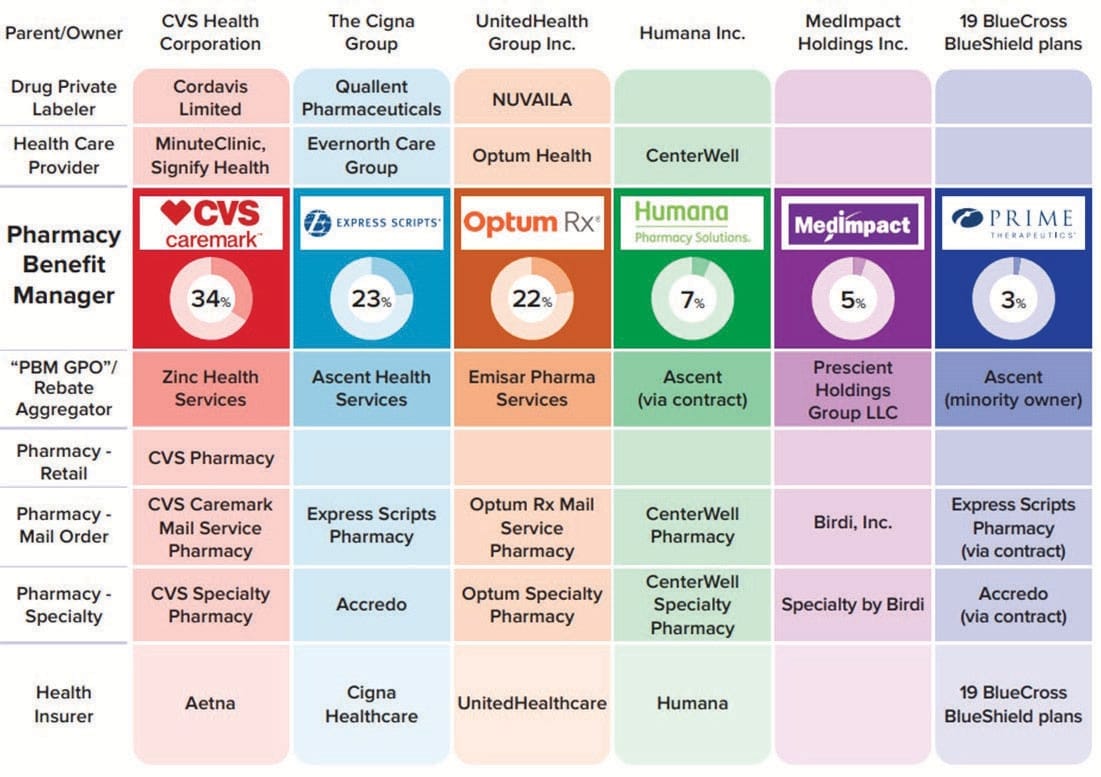

This matters, because mail order doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It is an extension of vertical integration — insurers owning PBMs, PBMs owning pharmacies, pharmacies shipping drugs automatically, and Medicare paying the bill.

I feel like a broken record mentioning this week after week.

New year. Same old system working exactly as designed.

Mapping out Vertical Integration in Pharma

How Oversupply Becomes Inevitable

Most of these shipments were 90-day supplies, sent early — often when patients were only 68% to 85% of the way through their previous fill.

Do the math.

Even conservatively, if you refill a 90-day prescription at the 85% mark, you get about 13 extra pills each time. Repeat that a few times a year, and suddenly a patient who takes one pill per day ends up with 400+ pills annually.

The surplus accumulates automatically.

Nobody sends the meds back or complains, because eventually they’ll probably need them. And they certainly don’t waste time calling and sitting on hold for an hour just to delay their next shipment. The system just keeps kicking the can down the road until, a few years later, patients have enough extra tablets to open their own pharmacy.

Why Mail Order is not the Enemy

Let’s be precise, because this is where the conversation usually goes wrong.

Mail-order pharmacies are not the root problem.

Even as a community pharmacy owner, I acknowledge that mail order can be convenient.

90-day supplies can improve continuity.

Automatic refills can help some patients.

The issue is who controls the rules — and who benefits when volume increases.

PBMs decide refill thresholds.

Insurers decide whether mail order is “preferred.”

Insurers own the mail-order pharmacies.

Dispensing more medication generates more revenue.

Mail order is simply the perfect execution layer: automated, frictionless, and detached from human judgment.

When a community pharmacy fills too early, a patient has to physically show up. A pharmacist has to hand them the bag. A conversation can happen. A transaction can be changed or reversed.

Mail order removes that friction entirely.

And in medicine, friction is often the safety feature.

The Adherence Excuse

When PBMs and insurers are challenged on early refills, the response is almost always the same:

Medication adherence.

The argument sounds reasonable. Patients who don’t miss doses are healthier. Missed doses cost the system money by preventing sickness and hospitalization. Early refills prevent gaps.

But there is also an uncomfortable truth underneath that justification.

Shipping medication early doesn’t just increase volume. It can also inflate adherence metrics, which are used to calculate Medicare Star Ratings.

Higher ratings mean:

Bonus payments from Medicare

Better plan marketing

Higher enrollment

In other words, oversupplying medication doesn’t just move inventory.

It makes the PBMs plans look better on paper.

That’s not patient-centered care.

That’s business.

The Risk isn’t just Waste — it’s Harm

The word waste doesn’t do this story justice.

Waste sounds accidental.

Waste sounds benign.

What the Journal documented carries real clinical risk, especially for older adults.

Is this a situation you would feel comfortable finding your grandmother in?

Extra pills increase the chances of:

Double dosing

Taking discontinued medications

Confusion when pill appearance changes

Accidental ingestion

Diversion

Many of the oversupplied drugs weren’t harmless vitamins. They included:

Muscle relaxants

Antipsychotics

Psychiatric medications

Drugs prescribed only “as needed”

Every pharmacist has seen the shoebox.

Every home-visiting physician has hauled away bags of old meds.

Every family has cleaned out a medicine cabinet after a death.

The Journal found that Medicare patients who died during the study period left behind an average of $240 worth of unused medication — $357(!) if they were served by UnitedHealth’s pharmacy arm.

That’s dangerous accumulation.

Follow the Money

This story makes sense the moment you stop looking at it as a pharmacy problem and start looking at it as a PBM and insurance problem.

PBMs and insurers design the refill rules.

They encourage automatic enrollment.

They own the dispensing channels.

They collect revenue per dispense.

And they shift profits from tightly regulated insurance arms into far less regulated pharmacy operations.

Medicare pays the bill.

Taxpayers absorb the cost.

No one in the system is financially punished for oversupplying drugs.

In fact, the incentives point in the opposite direction.

The Netflix Analogy

This is where the subscription analogy becomes unavoidable.

Netflix optimizes for continuity.

Auto-renew is the default.

The burden is on you to notice and stop it.

That’s annoying, but harmless.

PBMs and insurers have imported that exact logic into healthcare.

You’re opted into automatic refills.

Shipments creep earlier.

The system assumes continuation unless you actively intervene.

Except instead of a streaming service, the outcome is months or years of extra medication — and instead of a credit card charge, the cost is socialized across Medicare (AKA you and me).

The Number That Should Make You Mad

The Journal estimates this behavior cost Medicare and patients more than $3 billion over three years.

To put that in perspective:

When I pay taxes, painful as it may be, I like to imagine that the money I give the government is being put to good use.

Now imagine the taxes paid by you, your parents, your children, and everyone you care about — across multiple generations — being used to line the pockets of PBMs and insurance companies for oversupplying medication to senior citizens.

That’s what this $3 billion represents.

Again — our taxes used not to improve outcomes.

Not to save lives.

But to keep automated systems humming, balance sheets clean, and stock prices high for the biggest, most evil corporations in America.

This is not money that slipped through the cracks.

It moved exactly the way the system rewarded it to.

That should make us all livid.

Why This Matters

We’re constantly told PBMs exist to control costs.

Yet when the system they designed quietly generates billions in unnecessary spending — paid for by taxpayers — the conclusion is hard to avoid.

They aren’t controlling costs.

They’re controlling the flow of money.

Sometimes that means denying care.

Other times it means flooding homes with pills.

Different tactics. Same incentives.

And every time, the public pays.

Final Dose

Healthcare doesn’t just break when patients can’t get their medications.

It also breaks when the system won’t stop sending them.

This isn’t about careless seniors or greedy pharmacists. It’s about PBMs and insurers turning medicine into a subscription business — and charging Medicare for the privilege.

$3 billion is not a rounding error.

And it’s long past time we stopped pretending otherwise.

Alec Wade Ginsberg, PharmD, RPh

4th-Gen Pharmacist | Owner & COO, C.O. Bigelow

Founder, Drugstore Cowboy