Sponsored Serotonin

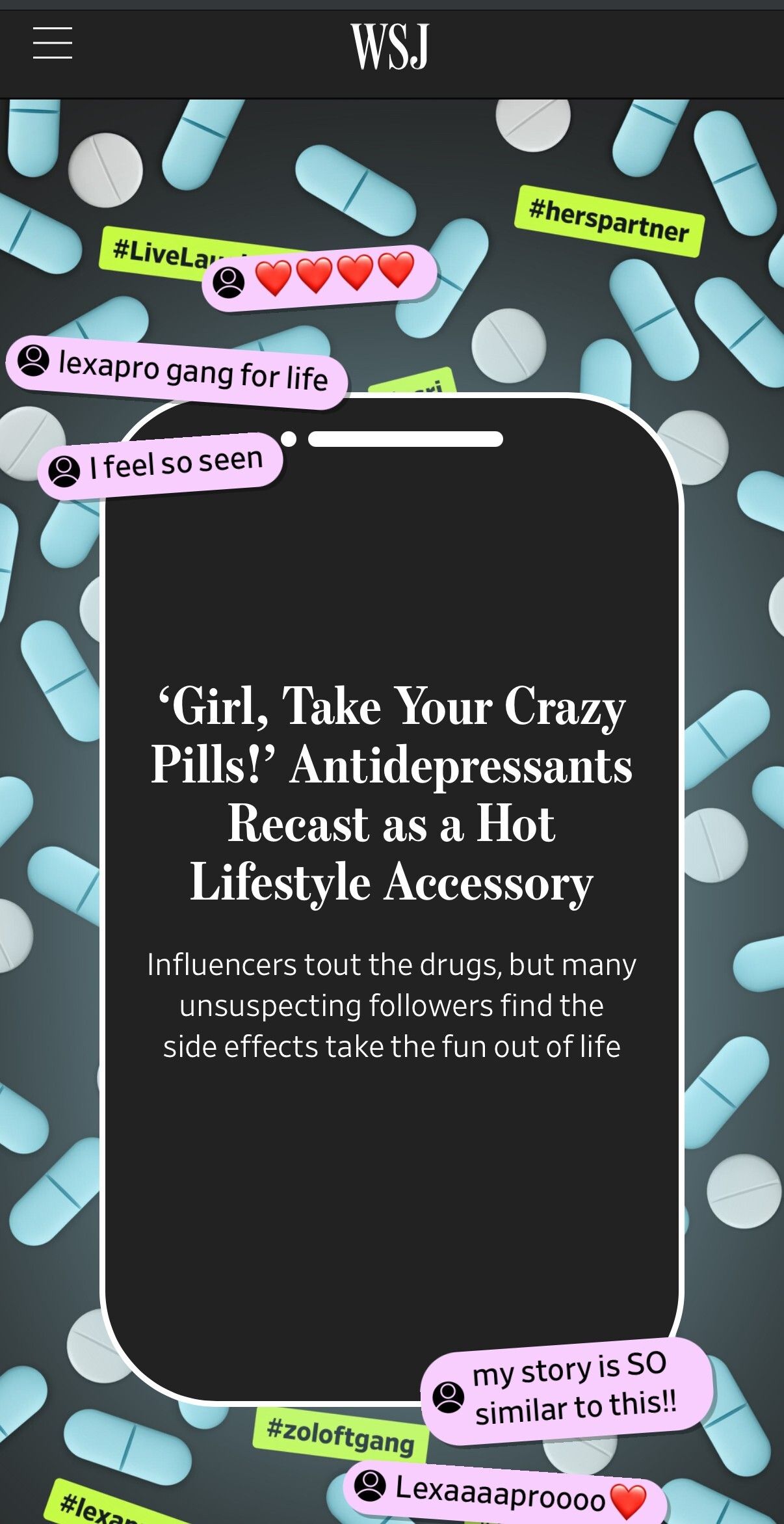

A few days ago, The Wall Street Journal published a story about influencers promoting antidepressants on TikTok—some paid by telehealth startups, others just swept up in the culture of #LexaproTok.

I don’t want to rehash that reporting or pass it off as my own. But it got me thinking about something bigger: the laws that are supposed to govern how drugs get advertised—and how social media has completely outrun them.

A few months ago, I wrote about how the U.S. is one of only two countries in the world that allows direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising. I gave a brief overview of the history of drug ads in this country and how it has gotten completely out of control.

If you subscribed to Drugstore Cowboy after that piece ran, I highly encourage you to go back and read it. It’s incredibly important for you, as a U.S. consumer, to understand how healthcare is being sold to you.

In that piece, my focus was on TV and Instagram/TikTok ads, where drug manufacturers create the content and target consumers. In that context, they’re required to disclose risks, side effects, and fine print at the bottom of the screen.

But what’s happening now is something different—and far more dangerous.

@alixearle Anywhoo i need to refill my lexapro

The new wave of pharmaceutical advertising doesn’t look like advertising at all.

It looks like a helpful recommendation from a trusted friend.

And that adds another level to the chaos.

The Loophole No One Talks About

When the FDA wrote its rules for drug promotion, the concept of a “creator economy” didn’t exist. The regulations were designed for glossy magazine spreads and 30-second TV spots—not for TikTok videos shot in bedrooms with pastel lighting and #selfcare captions.

Those rules still technically exist: any pharmaceutical company that advertises directly to consumers must present a “fair balance” of risks and benefits. They must name the drug, its intended use, and list potential side effects. That’s why television ads sound like legal disclaimers set to piano music.

But influencer marketing lives in a gray zone. The FDA’s jurisdiction covers drug manufacturers—not necessarily the people being paid to talk about the drugs. So when a telehealth startup like Hers or a third-party marketing agency pays an influencer to discuss her antidepressant “journey,” it’s often unclear who, if anyone, is responsible for making sure that message meets federal standards.

@nadyaokamoto Learning how important self-awareness and self-advocacy is when it comes to mental health treatment. @hers #TriedItAll Prescription produ... See more

When Pfizer runs a commercial, it has to list every side effect.

When your favorite creator gets paid to shake a Lexapro bottle on TikTok, the only thing she has to add is a #hashtag.

The New Faces of Pharma

According to The Wall Street Journal, Hims & Hers has spent more than $500 million on digital marketing since 2021, paying influencers between $3,000 and $10,000 per post to talk about their positive experiences with antidepressants online.

The resulting content often lives under hashtags like #livelaughlexapro, #zoloftgang, and #lexaprobaddies, blending medication into the language of empowerment and self-care. Some influencers disclose that the post is sponsored—with a tiny “#ad” or “#herspartner” buried in the caption—but some don’t even bother.

And to the average viewer, it doesn’t really matter.

These posts don’t feel like ads. They feel like advice.

That’s the danger. The traditional pharmaceutical commercial is easy to spot—you know you’re being sold something. But influencer marketing relies on trust, not persuasion. You follow someone because she seems real, relatable, maybe even like you. When she tells you Lexapro “changed her life,” it lands differently than a voiceover from Pfizer’s marketing department.

The messenger has become the message.

And in this new era, the boundary between authenticity and advertising has completely dissolved.

When the FDA Plays Catch-Up

The FDA’s last major social-media guidance was issued more than a decade ago—long before TikTok, influencer sponsorships, or telehealth platforms turned the internet into a medical marketplace.

Enforcement remains mostly symbolic. When the FDA finds a violation, the worst consequence is often a warning letter buried on its website. Meanwhile, the same companies can spend millions a month promoting drugs through “wellness creators” who aren’t legally bound by the same disclosure standards as traditional ads.

We’ve built a regulatory system for 30-second commercials.

But how many Americans under age 40 have even seen a “commercial” lately?

In the streaming era, commercial regulation isn’t protecting a majority of consumers anymore.

The real persuasion now happens in 30-second TikToks.

And the people making them don’t even realize they’ve become part of the pharmaceutical supply chain.

The Trust Problem

I’m not here to shame anyone who takes antidepressants. For many, these medications are essential and life-saving. The problem is the ecosystem forming around them—a marketplace where vulnerability is content and medication becomes a prop in someone else’s growth arc.

Influencer culture thrives on blurred boundaries: between authenticity and performance, advice and advertising, disclosure and omission. That might be harmless when we’re talking about vitamins or skincare. But when the product is a prescription, the stakes aren’t cosmetic—they’re chemical.

Telehealth companies know this. Their entire business model depends on collapsing the distance between seeing an ad and getting a prescription. A few clicks, a quick intake form, and a bottle arrives at your door. It’s convenience disguised as care—and when the marketing comes from someone you already trust, it barely feels like marketing at all.

The difference between a wellness ad and a drug ad shouldn’t depend on who’s holding the phone.

What’s at Stake

For decades, public trust in medication was built through doctors’ offices, pharmacies, and clinical data. Now it’s being rebuilt through algorithms.

The irony is almost too perfect: after years of destigmatizing mental-health treatment, we’ve managed to restigmatize honesty about its downsides. The same feeds that celebrate taking Lexapro for self-care rarely go viral when they reverse course months later and talk about withdrawal symptoms, weight gain, or emotional numbness. (These are many of the stories shared in the WSJ piece.)

Algorithms reward optimism, not accuracy.

And the result is a culture where disclosure has been replaced by aesthetic.

We don’t need less conversation about mental health.

We need fewer commercials masquerading as honest storytelling.

The Last Word

When I wrote about direct-to-consumer drug advertising earlier this year, I ended with a question:

So, here’s my challenge for all of you. The next time you hear those familiar words…

“Ask your doctor if [X] is right for you…”

try asking a different question:

“Why am I being sold a prescription in the first place?”

That question still applies—maybe now more than ever.

At least when a pharmaceutical company runs a TV ad, you know you’re watching one.

The new danger is that on social media, you might not.

Alec Wade Ginsberg, PharmD, RPh

4th-Gen Pharmacist | Owner & COO, C.O. Bigelow

Founder, Drugstore Cowboy