The Cost of Caring

A few days ago, Rite Aid quietly closed the doors to its last remaining stores — ending more than six decades as one of America’s largest pharmacy chains.

It’s tempting to shrug it off as just another corporate failure. Another retailer lost to debt, bad management, and Amazon.

But if you’ve been reading this newsletter, you already know that’s not what this is.

When even a multi-billion-dollar pharmacy with national contracts and PBM leverage can’t survive, it confirms what I’ve been shouting about:

The business of pharmacy in America has stopped making sense.

Who I Am, and Why I’m Writing This

If you’re new here — welcome. You’re in good company.

Over the last few weeks, Drugstore Cowboy has picked up thousands of new readers — and I’m incredibly grateful for all of you. The response has blown me away. It tells me people are starting to care about what’s happening behind the counter — even if they’ve never thought about it before.

So I wanted to take this opportunity to reintroduce myself.

My name is Alec Ginsberg, and I’m a pharmacist — yes, a real one.

That’s me being a pharmacist.

I run C.O. Bigelow Apothecary in New York City, the oldest operating pharmacy in America. My family has owned it since 1939, and I’m the fourth generation to continue the tradition.

I spend my days doing what pharmacists have always done: helping patients make sense of their medications, calling doctors when something doesn’t look right, and fighting insurance companies that seem allergic to common sense.

This newsletter started as an experiment. I wanted to explain the system I work inside — the one that’s collapsing beneath itself — in plain English for the average American consumer.

No corporate spin. No health-care-speak. Just the truth from someone who sees it up close.

Because the further I go in this profession, the clearer it becomes that we are losing something essential — and most people don’t even know it’s happening.

And yet, for all the frustration, I still believe in the work.

It’s not beyond saving.

The Patient Who Explains It All

Let me show you what I mean with a real-life example from my pharmacy.

One of my longtime patients — we’ll call him John — has been coming to C.O. Bigelow for over 20 years. He’s in his seventies, lives alone in the Village, and manages a complicated list of chronic conditions: HIV, diabetes, high blood pressure, and hypothyroidism.

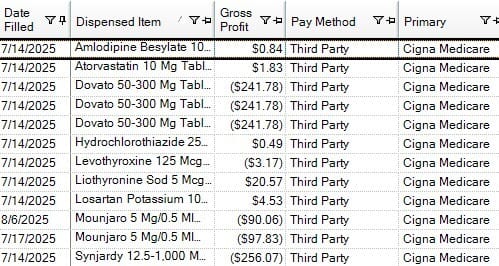

A snapshot of all John’s prescriptions for a 90-day period. Anything in parentheses under “Gross Profit” means the pharmacy is losing that amount of money on the fill.

He takes eight medications every day. They come from four different specialists across the city. His endocrinologist doesn’t always talk to his cardiologist. His infectious-disease doctor doesn’t always update his primary.

C.O. Bigelow is the common denominator.

We’re the ones who see the full picture — who flag interactions, adjust timing, and make sure a refill isn’t missed because one office forgot to fax something.

We remind him when his A1C is due. We notice when his blood pressure meds are being doubled by mistake. We even know which supplements make him feel sick.

That’s the part of pharmacy people still understand.

What they don’t see is what it costs to keep it alive.

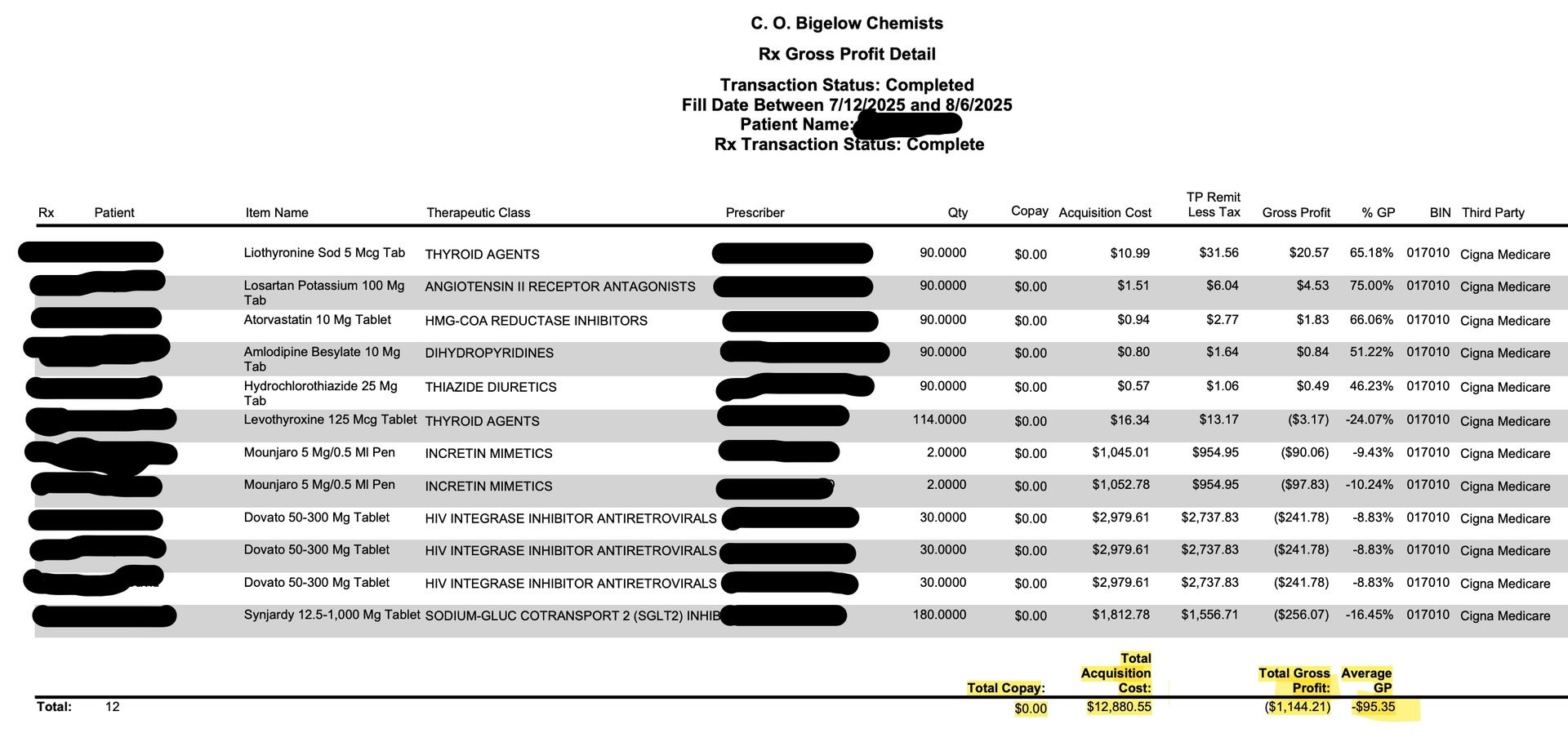

A single three-month fill of John’s medications costs our pharmacy about $15,000 in acquisition costs. The PBM reimbursement — what the insurance pays us back — is around $13,000.

That means every time we fill his prescriptions, we lose roughly $2,000.

A breakdown of John’s prescriptions that includes the pharmacy acquisition cost and our gross profit. Notice that John is on Medicare and all of his copays are $0. There is one Mounjaro fill missing from this screenshot, so the cost is actually greater and the gross profit is even worse.

Over the course of a full year, this represents a roughly $8,000 loss (on ~$60,000 spend!) just to keep one loyal patient on their meds.

That’s before labor, rent, and the dozens of small daily tasks that keep a 187-year-old pharmacy alive.

Now multiply that by hundreds of patients, and you start to understand why Rite Aid — a corporation with economies of scale, real estate holdings, and national distribution — couldn’t make the numbers work either.

The Math Doesn’t Lie — But It Also Doesn’t Care

A rational business owner would look at John’s account and say, “We can’t afford this.” And they’d be right.

But that goes against everything I stand for as a pharmacist.

Pharmacy — and all medicine, really — is a profession built on irrational compassion: the idea that you keep helping people even when it costs you.

You don’t tell someone with HIV to transfer their prescriptions elsewhere because their PBM contract pays you below cost.

You just figure it out. You take the hit and hope you can make it up somewhere else.

That’s what Rite Aid couldn’t do anymore.

That’s what thousands of independent pharmacies are struggling with right now.

And that’s why I started writing this newsletter — because these stories never make it into the glossy health-care headlines.

In fact, the very first piece I wrote when I launched was called “My Pharmacy’s $2 Million Ozempic Problem.”

In it, I explained in detail how C.O. Bigelow lost $26,000 in a single year on GLP-1s alone due to PBM reimbursements.

Different drug, same disease.

The PBM Problem, in Plain English

Every time I mention PBMs, I get emails from new readers asking: What exactly are they?

I recently wrote a five-minute explainer that I encourage everyone to read — but here’s the short version.

Pharmacy Benefit Managers are the middlemen that sit between your insurance company, your pharmacy, and the drug manufacturers.

They were supposed to negotiate lower prices for patients.

Instead, they’ve turned into shadow insurers that control which drugs get covered, how much pharmacies get paid, and who gets to stay in business.

They tell us what we’re “allowed” to dispense, at what price, and when we’ll get reimbursed.

They collect massive rebates from manufacturers — money you never see — and then reimburse pharmacies below cost.

That’s not hyperbole; it’s the business model.

And of course, they do all this without ever seeing a single patient.

So when a company like Rite Aid goes under, it’s not because customers stopped coming.

It’s because PBMs have engineered a system where filling prescriptions can be a loss-leading act of charity.

Why This Matters

When a pharmacy closes, patients lose more than convenience.

They lose continuity.

They lose the only person who still knows their full medication list.

They lose someone who notices when a new drug conflicts with an old one, or when a dosage seems off, or when something about their lab work doesn’t add up.

They lose the human part of medicine.

And once a pharmacy disappears, it doesn’t come back.

The chains consolidate, mail-order grows, and the system becomes just a little more robotic.

Healthcare loves to talk about “innovation.”

But most of that innovation is designed to replace the human element, not support it.

It’s all about cutting costs instead of improving care.

The Businessman vs. the Pharmacist

This is the part that keeps me up at night.

As the owner of a 187-year-old business, I’m supposed to think like a businessman.

Protect margin. Watch payroll. Optimize inventory.

But as a pharmacist, my instinct is to take care of people — even when it doesn’t make financial sense.

So when I look at John’s profile, I see both truths at once:

He’s a loyal patient who’s trusted us for decades.

And he’s a financial liability that’s slowly killing my business.

That’s the moral trap of modern pharmacy.

You can be profitable, or you can be compassionate — but it’s getting harder to be both.

And when your pharmacy has 500 Johns, it becomes impossible to function at all.

Why Rite Aid Fell — and Why I’m Still Here

Rite Aid didn’t fall because it was inefficient or outdated.

It fell because the economics of dispensing medicine are upside down.

It fell because PBMs have turned every prescription into a race to the bottom, where the only winners are the middlemen taking a cut on both sides.

And the same forces that killed Rite Aid are coming for everyone else.

When a neighborhood pharmacy disappears, it doesn’t make headlines.

It just quietly stops answering the phone one day.

Why I Keep Writing

Drugstore Cowboy exists because I believe people deserve to understand what’s happening — not from a lobbyist or a press release, but from someone still behind the counter.

I’m not writing this to romanticize the past.

I’m writing it because I see what’s coming.

Because if we don’t start paying attention, we’ll wake up in a country where it’s easier than ever to get a pill delivered to your door — but no one left who actually knows what you’re taking, or why.

This newsletter is my way of saying: there’s still a real person here.

I’m still filling prescriptions.

I’m still fighting PBMs.

I’m still trying to make the math work without losing my humanity.

And if Drugstore Cowboy helps more people see that — helps more people care — then maybe there’s still hope for the American drugstore.

Because someone has to keep the lights on.

Giddy up.

Alec Wade Ginsberg, PharmD, RPh

4th-Gen Pharmacist | Owner & COO, C.O. Bigelow

Founder, Drugstore Cowboy